Current National Data on Framing Lumber Markets

Originally Published by: NAHB — August 26, 2024

SBCA appreciates your input; please email us if you have any comments or corrections to this article.

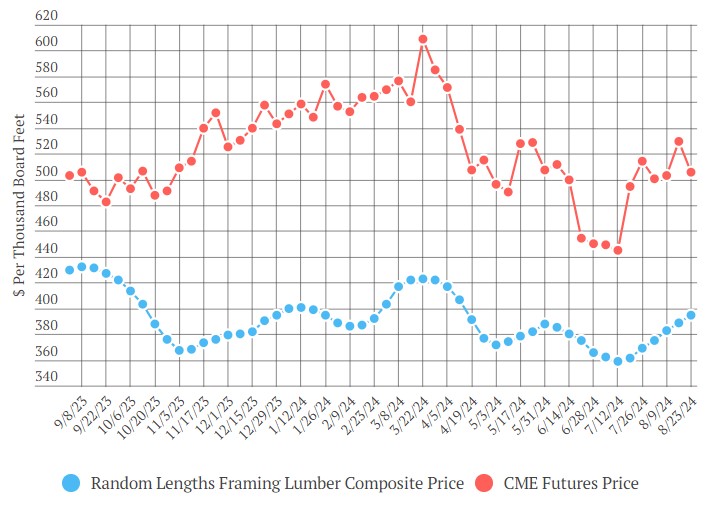

The framing lumber composite price rose 1.5% during the week ending Aug. 23. After dropping to their lowest level since April 2020, lumber prices have now risen for six consecutive weeks.

NAHB continually tracks the latest lumber prices and futures prices, and provides an overview of the behaviors within the U.S. framing lumber market. The information is sourced each week using the Random Lengths framing lumber composite price which is comprised using prices from the highest volume-producing regions of the U.S. and Canada. A summary of other wood prices, including plywood prices, is included below.

Prices and Trends in the U.S. Framing Lumber Market

Summary of the week-to-week lumber prices and plywood prices for the week ending Aug. 23, 2024:

- The Random Lengths framing lumber composite price rose 1.5% from the previous week.

- Prices are up 7.0% in the past month, but they are still 6.8% lower than one year ago.

- Thus far, 2024 has been the least volatile year for lumber prices since 2019.

- The price of lumber futures fell 4.4%, and the continue trading at a premium of over $100.

- Prices are 1.9% lower than a year ago.

- The structural panel composite price rose 0.8% from the previous week.

- OSB prices increased 0.9%.

- Western Fir plywood prices were flat.

- Southern Yellow Pine plywood prices increased 2.0%.

Key Factors Influencing Lumber Prices

Softwood lumber prices have been especially volatile in recent years largely because of increased demand, rising tariffs, supply-chain bottlenecks and insufficient domestic production. To address the high prices for lumber, NAHB has advocated for the following actions:

- Negotiate a long-term deal with Canada to reduce tariffs and boost imported lumber.

- Increase domestic production by seeking higher targets for timber sales from publicly-owned lands and opening up additional federal forest lands for logging.

- Reduce U.S. lumber exports to China and other international clients.

- Seek out new markets to reduce our nation’s reliance on Canadian lumber imports and make up for our domestic shortfall.

- Identify new markets (besides Canada) and work with countries already exporting softwood lumber to the United States to increase their exports here.

Impact of Wood and Lumber Prices on the Cost of a New Home

In addition to narrowly defined framing lumber, products such as plywood, OSB, particleboard, fiberboard, shakes and shingles make up a considerable portion of the total materials (and cost) of a new home.

Surveys conducted by Home Innovation Research Labs show that the average new single-family home uses more than 2,200 square feet of softwood plywood, and more than 6,800 of OSB, in addition to roughly 15,000 board feet of framing lumber. Softwood lumber is also an input into certain manufactured products used in residential construction — especially cabinets, windows, doors and trusses.

To account for the manufacturer’s margin, sawmill prices for the lumber embodied in these products are marked up by the percent difference between receipts and cost of goods in the "wood product manufacturing" industry, as reported in the IRS Returns of Active Corporations tables.

Final pricing for home buyers is somewhat higher because of factors such as interest on construction loans, brokers’ fees, and margins required to attract capital and get construction loans underwritten. As explained in NAHB’s study on regulatory costs, for items used during the construction process, the final home price will increase by nearly 15% above the builder’s cost.

The bottom line is that changes in softwood lumber prices directly impact the price of a new home. This, along with rising wages for construction workers and higher interest rates, is one of the reasons the housing market is experiencing declining affordability.

When Do Lower Lumber Prices Reach Builders?

Homebuilders and remodelers begin to get price relief once mill prices have substantially decreased for an extended period and/or stabilized. Note that large price decreases alone may not be sufficient. Prices must fall for long enough periods of time to sufficiently lower a supplier’s average costs after a run-up.

Depending on the rate and consistency of price decreases and whether prices have stabilized at the lower level, it may take at least a few weeks to a couple of months for builders to see price relief on the order initially reported in the lumber futures or cash markets.

The length of this “waiting period” for lumber price reductions varies with builder size, supplier size, and the specific builder-supplier relationship. Buying power is positively correlated with the size of a residential construction firm, while the same is typically true for suppliers’ selling power. The relative difference in market power between the buyer and seller is crucial in determining how quickly lower prices transmit to a customer.

Why Do Builders’ Lumber Costs Rapidly Increase with Market Prices?

In contrast to the dynamics of an environment with falling prices, higher prices reach builders much more quickly when market prices are increasing. The same forces that lead to large lags relative to mill prices on the way down can help explain why builders’ lumber costs may increase contemporaneously with mill prices.

Wholesalers tend to be “trigger happy” when prices skyrocket. As the cost of their inventory is low relative to cash prices during these periods, they will quote at or near current market prices. The environment is one in which wholesalers are assured to buy low and sell high.

However, wholesalers cannot predict when a bull market is going to end and buy their lumber according to how likely they believe it will last. As different buyers may have different forecasts, disparities in purchasing behavior can arise. A wholesaler who assumes lumber prices will keep rising for two months will buy more inventory than one assuming the run will last for only two weeks.

Retailers generally have less buying power than wholesalers have selling power. In such a scenario, the retailer (e.g., lumberyard) is said to be a “price taker.” As a result, their inventory costs tend to increase in step with market prices.

These higher costs are passed on to builders in order to maintain positive operating margins. This is why lumber retailers are less likely than wholesalers to realize outsized profits when prices are rising.