As Expected, Fed Raises Rate an Additional 75 Basis Points

Originally Published by: NAHB — September 21, 2022

SBCA appreciates your input; please email us if you have any comments or corrections to this article.

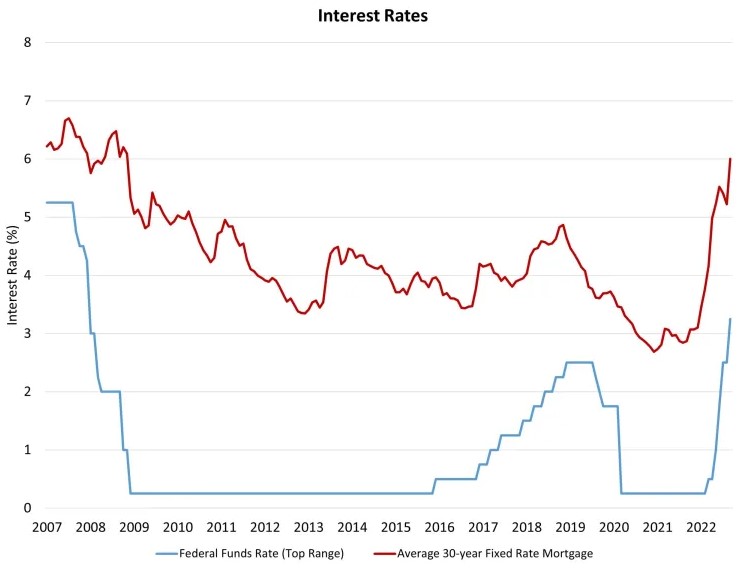

Continuing its tightening of financial conditions to bring the rate of inflation lower, the Federal Reserve’s monetary policy committee raised the federal funds target rate by 75 basis points, increasing that target to an upper bound of 3.25%. This marks the third consecutive meeting with an increase of 75 basis points. These supersized hikes are intended to move monetary policy more rapidly to restrictive policy rates. And the Fed’s leadership has signaled they intended to hold these elevated rates for a substantial period time, well into 2024.

While committing to a increasingly hawkish policy path that will slow demand and reduce inflation, the Fed also acknowledged that the economy is only growing at a “modest” pace. Moreover, their projections note that the unemployment rate will increase to 4.4% in 2023 (this is an optimistic forecast; NAHB projects a rate near 5% at the start of 2024). The Fed has over the course of recent meetings raised its expectations for the top rate for 2022 from 3.4% to 4.4%.

Looking forward, the Fed’s “dot plot” indicates that the central bank expects the target for the federal funds rate will increase by 75 more basis points in November, 50 in December, and then concluding with 25 points at the start of 2023. This would take the federal funds top rate to to near 4.8%. Combined with quantitative tightening from balance sheet reduction (in particular $35 billion of mortgage-backed securities (MBS) per month), this represents a significant amount of monetary policy tightening over a short period. Given this policy path, a hard landing with a mild economic recession is all but unavoidable to bring inflation back to the Fed’s target. By 2025, the Fed is forecasting a return to a normalized rate of 2.5% for the federal funds rate.

Among the clear signs of economic slowing are just about every housing indicator, including nine straight months of declines for home builder sentiment. Indeed, an open macro question is whether the economy experienced a recession during the first half of 2022, during which the economy posted two quarters of GDP declines. The missing element from the recession call: a rising unemployment rate, which is coming. Regardless, given declines for single-family permits, single-family starts, pending home sales, and rising sales cancellations rates, it is clear a housing industry recession is ongoing. The pain of this is clear in terms of the large economic impact housing has on the overall economy.

Housing (shelter costs) is also key to the risk of the Fed raising rates too high for too long. Elevated CPI readings of inflation will occur going forward because paid rents will take time to catch-up with prevailing market rents as renters renew existing leases. This lag means that CPI will show inflationary gains months after rent growth has in fact cooled. The core PCE measure, which peaked in 2022, is better indicator of inflation and suggests the current Fed outlook may be too hawkish.

It is important to note that there is not a direct connection between federal fund rate hikes and changes in long-term interest rates. During the last tightening cycle, the federal funds target rate increased from November 2015 (with a top rate of just 0.25%) to November 2018 (2.5%), a 225 basis point expansion. However, during this time mortgage interest rates increased by a proportionately smaller amount, rising from approximately 3.9% to just under 4.9%. The 30-year fixed mortgage rate, per Freddie Mac, is near 6% today. The expected additional tightening from the Fed is likely to take this rate above 6.5% before the end of the year.

Moreover, the spread between the 30-year fixed rate mortgage and the 10-year Treasury rate has expanded to approximately 260 basis points as of last week. Before 2020, this spread averaged a little more than 170 basis points. This elevated spread is a function of MBS bond sales as well as uncertainty related to housing market uncertainty.

Finally, the Fed has previously noted that inflation is elevated due to “supply and demand imbalances related to the pandemic, higher energy prices, and broader price pressures.” While this verbiage may incorporate policy failures that have affected aggregate supply and demand, the Fed should explicitly acknowledge the role fiscal, trade and regulatory policy is having on the economy and inflation as well.