Charts: Understanding the U.S. Historic Housing Shortage

Originally Published by: NAHB — December 16, 2022

SBCA appreciates your input; please email us if you have any comments or corrections to this article.

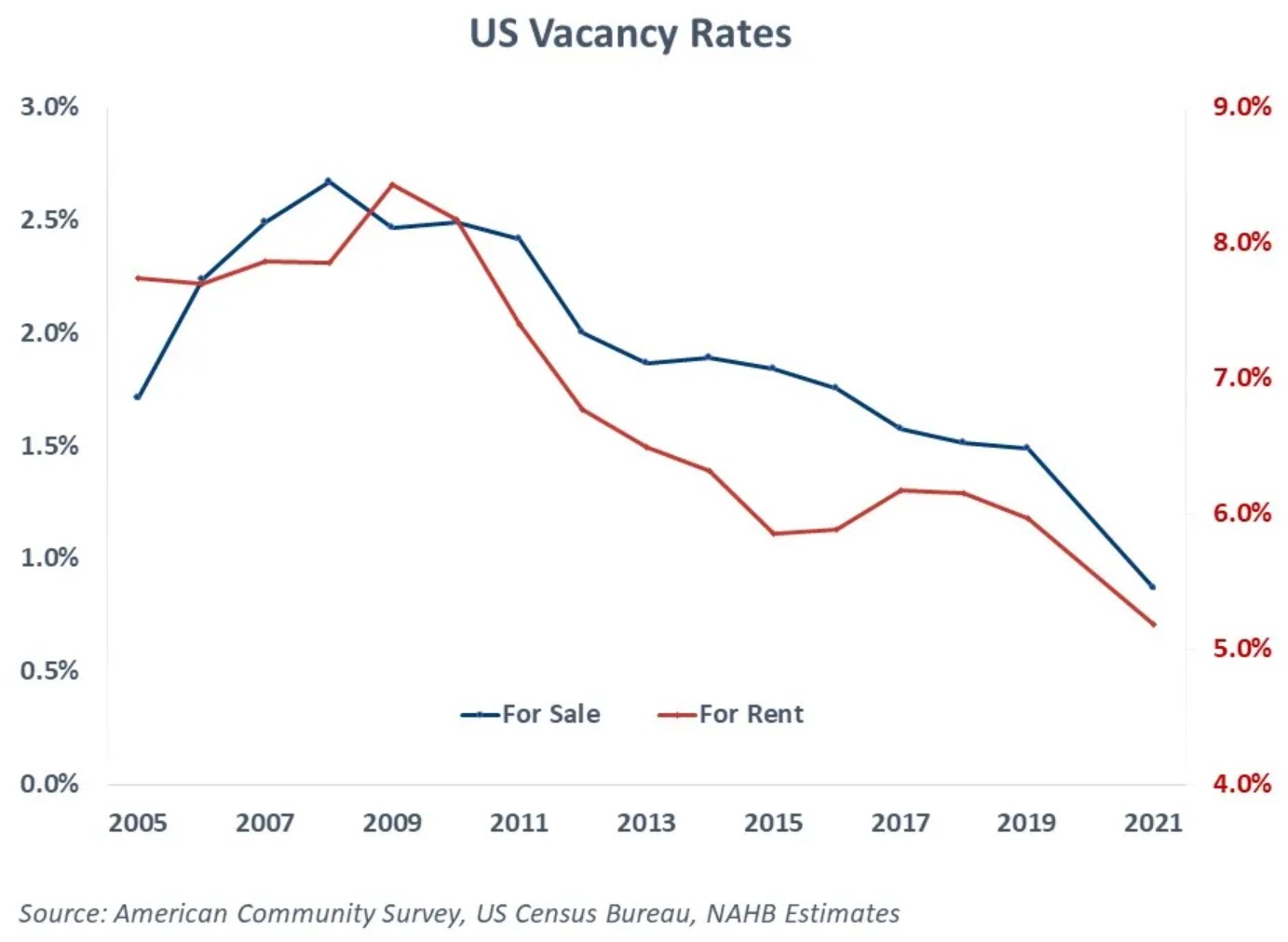

Reflecting the unprecedented housing shortages across the United States in the post-pandemic market, U.S. vacancy rates hit their lowest readings in decades in 2021. According to NAHB’s analysis of the 2021 American Community Survey (ACS), owner vacancy rates dropped below 0.9% and rental vacancy rates reached a new low of 5.2%, the lowest levels recorded by the ACS since the survey started generating these data in 2005.

Comparing current abnormally low vacancy rates with long-run typical rates across metro markets of the U.S., NAHB now estimates that 1.5 million units are required to close the gap and bring the current vacancy rates back to the long-run equilibrium levels. This is our revised estimate for the size of the structural housing deficit in the U.S. It indicates the amount of above equilibrium home building required to bring the market back into long-run balance. NAHB’s forecast indicates that this will take place between 2025 and 2030.

Homeowner and rental vacancy rates are one of the key statistics that are used to judge the health and direction of the housing market. The current low homeowner and rental vacancy rates are typically interpreted as a sign of tight housing markets, with abnormally low vacancy rates signaling a greater housing shortage. The ACS data allow estimating vacancy rates across metropolitan areas and identifying metro housing markets where unusually low vacancy rates signal deeper supply-demand imbalances.

The “long run” average vacancy rates can serve as a proxy for normal, or natural, vacancy rates. There are numerous reasons why normal vacancy rates may differ across metropolitan areas. For example, areas with mobile labor markets and higher population turnover will consistently have higher vacancy rates. Vacation destination housing markets also have naturally higher vacancy rates that reflect more volatile seasonal housing demand. For example, according to NAHB’s estimates, the rental vacancy rates in Ocean City, NJ, Panama City, FL and Sebastian-Vero Beach, FL fluctuated around 20% since 2005. The averages were even higher in Myrtle Beach, SC, fluctuating around 30%. In sharp contrast, multiple areas in California, including Santa Maria-Santa Barbara, Santa Cruz-Watsonville, San Jose-Sunnyvale-Santa Clara, San Luis Obispo-Paso Robles-Arroyo Grande, Oxnard-Thousand Oaks-Ventura, and Los Angeles-Long Beach-Anaheim, CA, registered long-term rental vacancy rates below 4%.

In case of homeowner properties, natural vacancy rates are typically smaller, simply reflecting slower housing turnover with owners moving in and out less frequently compared to renters. It is important to keep in mind that owned seasonal (occasional use) properties do not affect the homeowner vacancy rate. In this case, the vacancy rate is the share of vacant units for sale in the combined stock of homeowner occupied, sold but not yet occupied, and for sale units. Thus, vacation or other seasonal properties are excluded from this analysis.

Nevertheless, the long-run homeowner vacancy rates tend to be higher in resort areas. Once again, Ocean City, NJ and multiple metro areas in coastal Florida register some of the highest long-run owner vacancy rates. In Naples-Immokalee-Marco Island, FL, Sebastian-Vero Beach, FL, Punta Gorda, FL, owner vacancy rates fluctuated above the 4% mark since 2005. In Ocean City, NJ they averaged 6%, the highest rate among the metro markets. At the opposite end of the spectrum is San Jose-Sunnyvale-Santa Clara, CA where owner vacancy rates were below 1% most of the time.

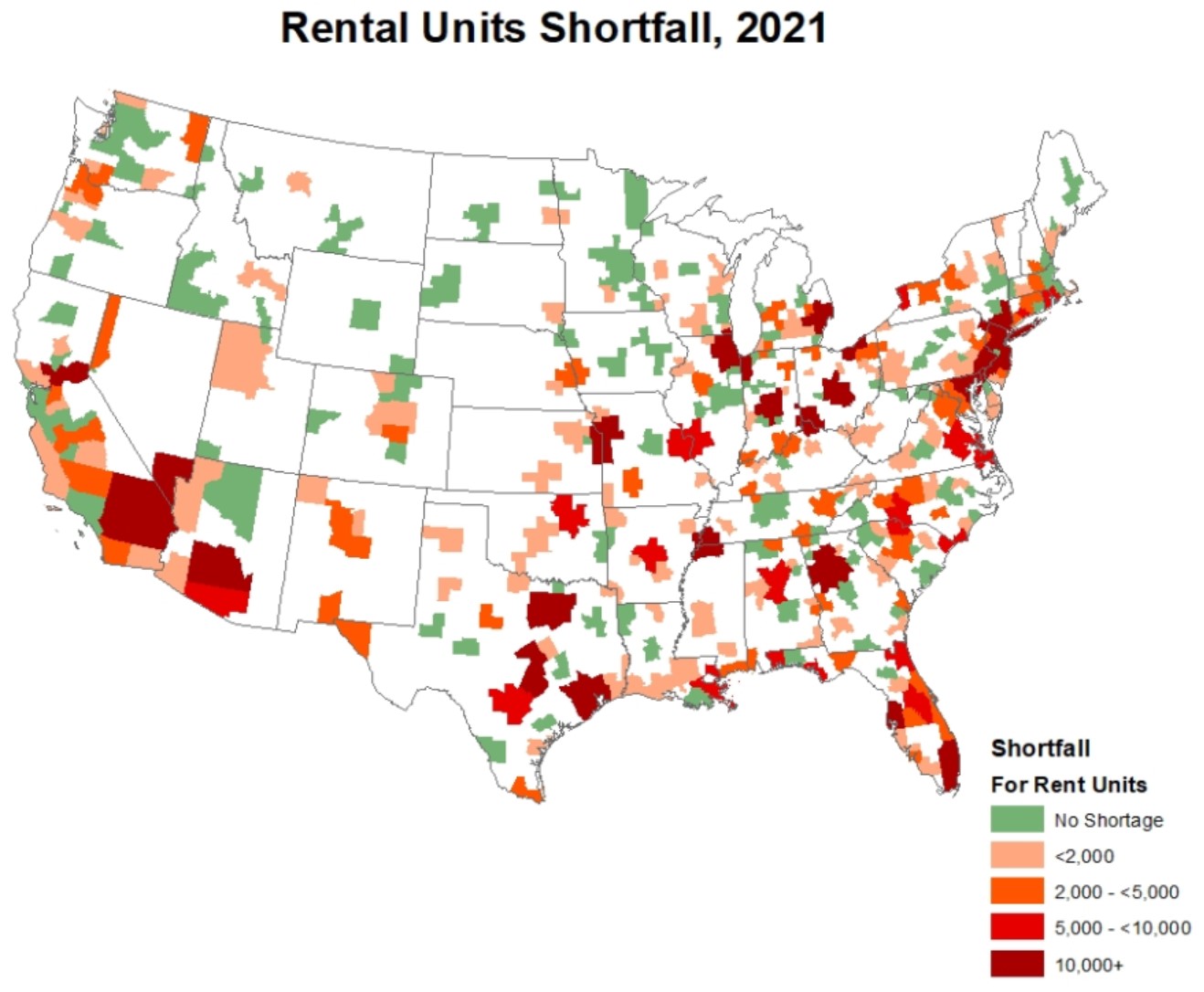

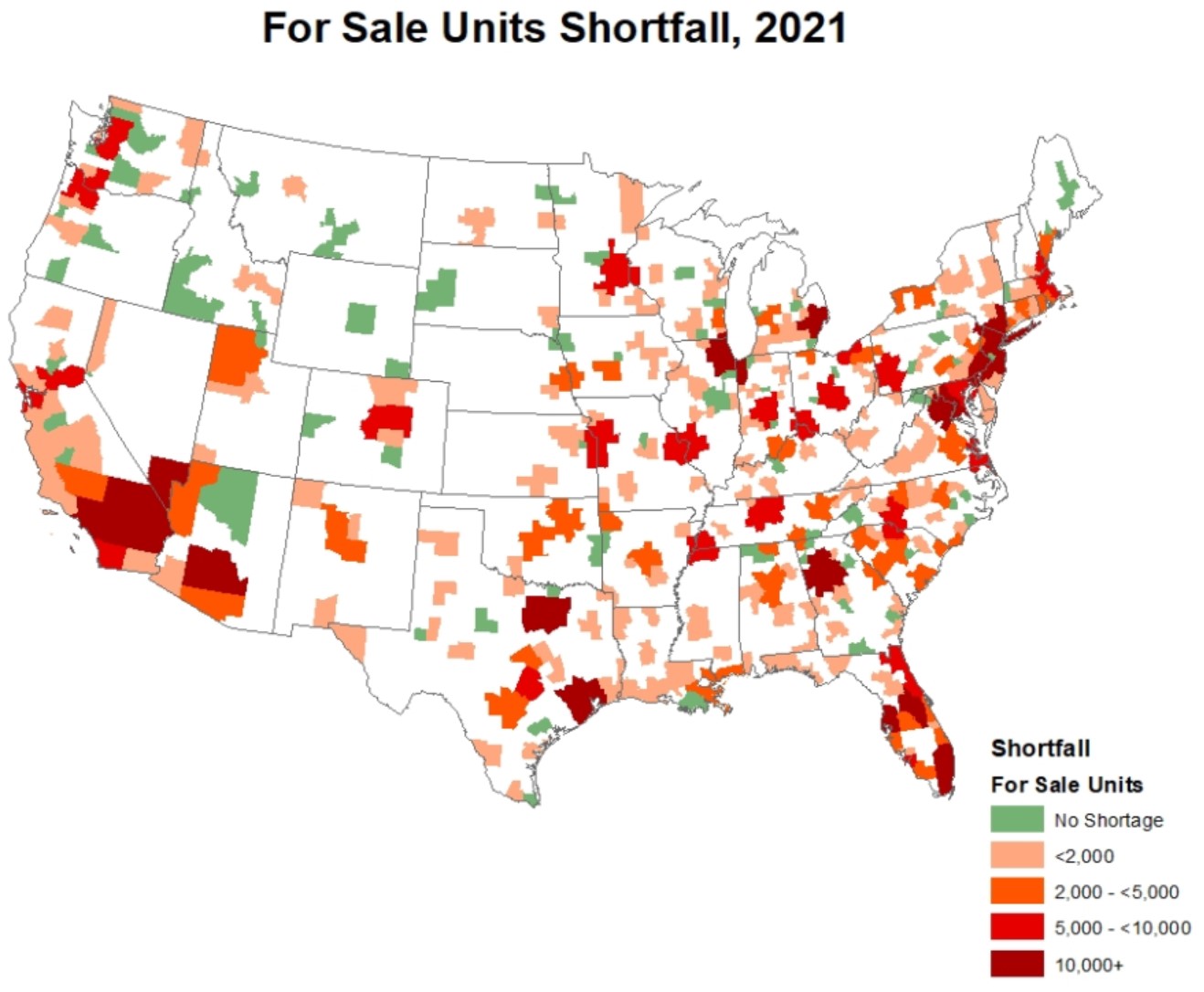

The gap between the “natural”, or long-run average, and current vacancy rate allows estimating the number of rental and for sale units needed to bring the vacancy rates back to the long-run equilibrium. Not surprisingly, large metro markets show the largest shortage of rental and for sale vacant units simply due to the sheer size of these housing markets. In these areas, even a small percentage drop below the long run average vacancy rates results in a shortage of thousands of vacant units.

As of 2021, Dallas-Fort Worth-Arlington, TX, needed close to 34,000 rental units just to bring the rental vacancy rate back to normal levels. The rental shortages in Phoenix-Mesa-Chandler, AZ, Miami-Fort Lauderdale-Pompano Beach, FL, and Atlanta-Sandy Springs-Roswell, GA were around 29,000 units.

Similarly, the biggest shortages of vacant units for sale were registered by large metropolitan areas, including Atlanta-Sandy Springs-Roswell, GA, Chicago-Naperville-Elgin, IL-IN-WI, New York-Newark-Jersey City, NY-NJ-PA, Phoenix-Mesa-Scottsdale, AZ, Miami-Fort Lauderdale-West Palm Beach, FL.

Adding up the vacancy shortages across metro areas with abnormally low vacancy rates, there is a shortage of about 1.5 million vacant units (800,000 rental and 750,000 units for sale) nationwide.

The above estimates only evaluate shortages of vacant units needed to bring the current vacancy rates back to the normal levels and do not attempt to include the additional housing shortfall due to pent-up housing demand or need to replace the aging stock. Additionally, these estimates measure a different concept than current market inventory, which is rising currently due to declines for housing affordability. That is a cyclical measure which will fall when the Fed normalizes interest rates.

Finally, all attempts to estimate the structural housing deficit are subject to some error depending on that data source used and assumptions deployed. For example, do ADUs count as perfect substitutes for apartment or entry-level single-family homes. Does the share of young adults living with family remain constant? These are not easy questions, but we believe the estimates in this post provide a reasonable, revised national estimate of the current housing structural deficit.