Fed Pauses Rate Hikes, but What Might Be Next?

Originally Published by: Builder — June 14, 2023

SBCA appreciates your input; please email us if you have any comments or corrections to this article.

The Federal Reserve elected to pause on short-term rate increases during its June meeting. The Fed’s pause is intended to allow time for its current policy to filter into the economy. Importantly, the Fed wants to see if the strong labor market, resilient housing market, and persistently high inflation levels cool as expected or remain elevated.

The Fed has four more meetings this year where they must decide what they believe to be the appropriate next steps for policy. They have one of three choices:

- Hike. The Federal Reserve can opt to resume raising interest rates if it believes it hasn’t seen enough signs of the economy slowing. By raising interest rates, the Fed would be carrying on with what is known as contractionary, or tightening, policy.

- Pause. The Fed can pause again if it believes the current level of interest rates, known as the federal funds rate, is “sufficiently restrictive.” This means they feel confident that the current rates will be able to slow growth to more healthy levels. The Fed has made it clear, though, that despite the pause, this does not mean they won’t resume raising rates later this year depending on how the incoming data looks. If this is the case, the current policy stance could be viewed as a “skip” instead of a true “pause.”

- Cut. If the Fed believes that the economy has slowed dramatically, or has even fallen into a recession, it can start lowering interest rates. This would be a shift to what is known as expansionary, or loosening, policy where it is trying to stimulate growth.

Given the intense interest regarding the Federal Reserve’s next steps, we have gathered information on past cycles to educate around what has happened previously and to help inform as to what might happen next.

For the purposes of our research, we will be looking at all the tightening cycles over the past 30 years. During that period, the Fed has historically raised rates for an average of 19 months, 11 months on the short end and 36 months on the long end—defining a tightening cycle from the first rate hike to the last rate increase. We are 15 months into the current cycle.

The average tightening cycle in our research window has been 10 rate increases. There already have been 10 hikes in the current tightening cycle that started in March 2022. This cycle has been different than the past in a number of ways though:

- Unusually large increases. Nearly 80% of the rate increases since 1990 have been 25 basis points (bps), making a quarter-point percent increase the typical size of rate hikes. The distribution of rate increases from past tightening cycles since 1990 is: 78% 25 bps, 12% 50 bps, and 10% 75 bps. The distribution this cycle has been: 40% 25 bps, 20% 50 bps, and 40% 75 bps.

- Pushing rates to restrictive territory. The cumulative size of the hikes has been larger than usual, with the current increase at 4.75%. This is larger than the recent tightening cycles that averaged about 2.9%. For context, short-term rates increased 4.25% in the mid-2000s.

- Not historically unprecedented. The current rate increase is still much less than the 1970s and early 1980s when rates increased 13% from January 1977 to April 1980 and 10.1% from July 1980 to January 1981. This is an interesting, but imperfect, period of comparison given the cycles then and now were both driven by elevated levels of inflation. Inflation peaked at higher levels and remained elevated for longer in the 1970s and 1980s, though.

- Starting from zero. The only other time we’ve raised short-term interest rates from an extended period at 0% is following the Great Financial Crisis.

Once the rate increases stop, the average pause before rate cuts over the past 30 years has been just over 10 months, with a range of five months to 18 months.

If history were to hold, a reasonable range for the first cut this cycle would be November 2023 to December 2024. This “pause” actually being a “skip” with more increases later this year would result in a pushed back timeline.

Once the cuts start, the loosening cycles, defined as the first rate cut to the last rate decrease, last from seven to 30 months with 14 months being the average. The typical rate cut is 0.25% (60% of the cuts since the 1990s have been this size), and the average number of rate cuts during the loosening cycle is nine.

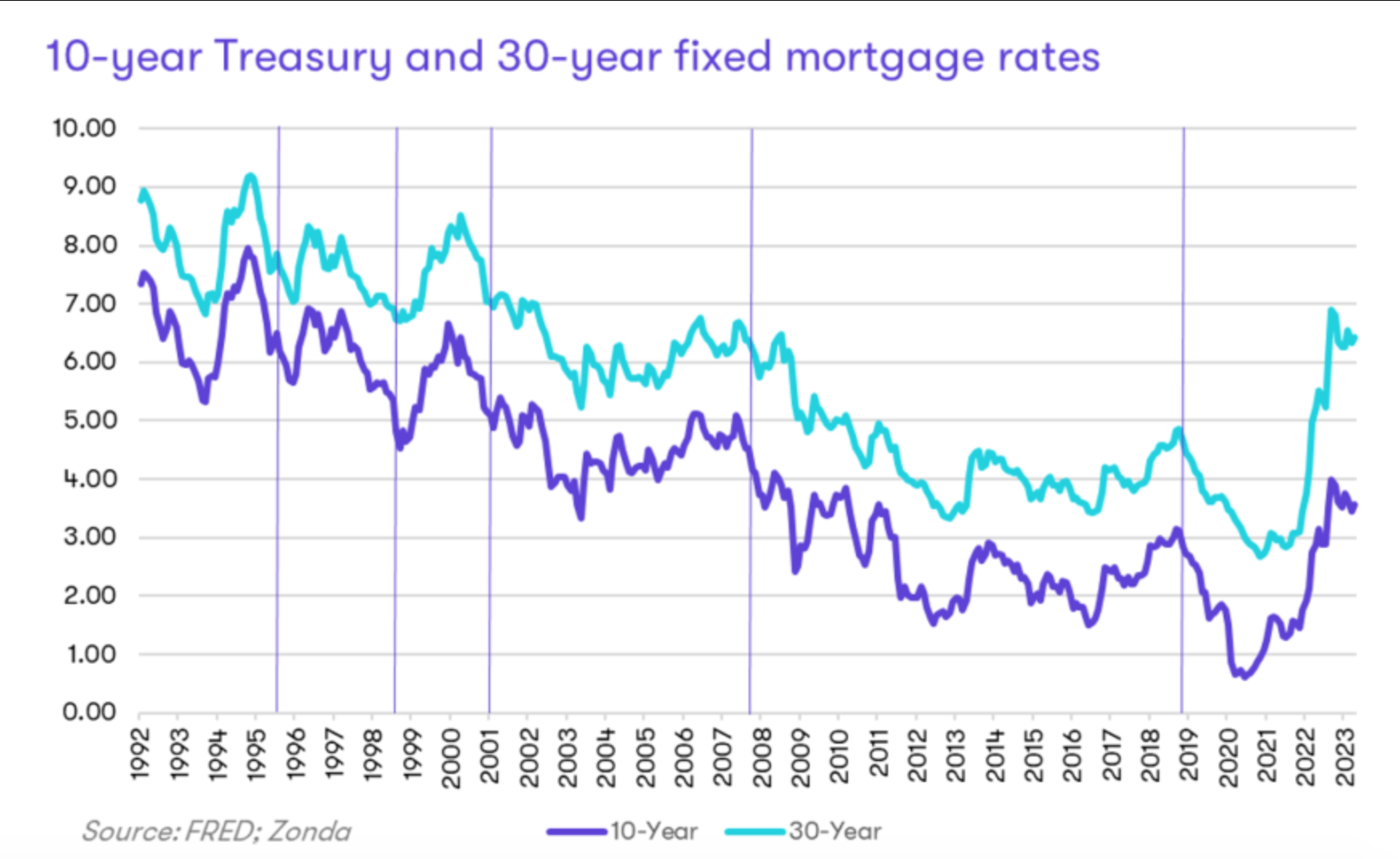

Important to the home building industry is the impact on mortgage rates, shown in the graph below. The vertical purple bars are the approximate dates of the cuts. Notice that, typically, the cuts occur after the 10-year and 30-year mortgage rates have already started to decline.

We interpret this as traders reacting in advance of monetary policy, taking into account current economic conditions and projections. The 10-year Treasury yield and mortgage rates typically trend down in recessions, a condition often, but not always, accompanying rate cuts. In fact, rate cuts led the official starts of recessions by three months on average. Once the recessions ended, the Fed did not hike again for an additional 42 months. These four years are typically an expansionary period for the economy.

Mortgage rates are historically down 17% from peak at the start of the cuts and then hold relatively flat for the next year: Rates are historically 18% off peak three months after the start of the cuts, 19% off peak six months later, and 17% off peak 12 months later. Applying the math to today’s market, this could put mortgage rates back in the 5%s as a rate cut approaches. Remember, the mortgage rate spread compressing is another path to see mortgage rates come down as well. Lower mortgage rates aren’t guaranteed, especially if inflation doesn’t cool more, but there are some reasonable paths in that direction over the next 12 to 24 months.

Chair Powell opaquely suggested a pause may be on the way after the last Federal Open Market Committee meeting in May, and the FOMC followed through with a hold. Moving forward, we predict a low probability that the Fed will cut rates this year unless the economy takes a dramatic turn to the negative over the next six months.