Seeing the Lumber Amongst the Trees

Understanding lumber grading and stamps is critical to a CM’s success

Understanding lumber grading and stamps is critical to a CM’s success

Included in the cutting-edge software used to design roof and floor trusses are engineering principles outlined in the National Design Specification, Design Values for Wood Construction (NDS), as well as the published design values for the sizes and grades of softwood lumber used in North America. For component manufacturers utilizing truss design software, it’s important to know how those published design values are derived and how they impact truss designs, as well as understand the impact subtle differences between species groups have on expected truss performance.

How Lumber Design Values are Established

The NDS Supplement provides a succinct description of the published lumber design values:

“Reference design values for most species and grades of visually graded dimension lumber are based on provisions of ASTM Standard D 1990-16 (Establishing Allowable Properties for Visually Graded Dimension Lumber from In-Grade Tests of Full-Size Specimens)…Reference design values for machine stress rated (MSR) lumber and machine evaluated lumber (MEL) are based on nondestructive testing of individual pieces…The stress rating systems used for MSR and MEL lumber is regularly checked by the responsible grading agency for conformance to established certification and quality control procedures.”

In other words, softwood lumber species groups are regularly subjected to established testing protocols to ensure the published design values are present in the lumber that is produced. In North America, there are six grading agencies that have jurisdiction over establishing softwood lumber design values and are responsible for conducting ongoing testing to verify them. They are: National Lumber Grades Authority (NLGA), Northeastern Lumber Manufacturers Association (NeLMA), Redwood Inspection Services (RIS), Southern Pine Inspection Bureau (SPIB), Pacific Lumber Inspection Bureau (PLIB/WCLIB), and Western Wood Products Association (WWPA).

Each of these grading agencies follow grading rules approved by the American Lumber Standard Committee’s (ALSC) Board of Review (BOR) and are certified for conformance with the U.S. Department of Commerce Voluntary Product Standard (VPS) process. For softwood lumber used in the U.S., the VPS is maintained by the ALSC and is referred to as American Softwood Lumber Standard PS 20 (PS 20). The current edition is PS 20-20, which can be found at: https://bit.ly/3VY6vHi.

Each of these grading agencies follow grading rules approved by the American Lumber Standard Committee’s (ALSC) Board of Review (BOR) and are certified for conformance with the U.S. Department of Commerce Voluntary Product Standard (VPS) process. For softwood lumber used in the U.S., the VPS is maintained by the ALSC and is referred to as American Softwood Lumber Standard PS 20 (PS 20). The current edition is PS 20-20, which can be found at: https://bit.ly/3VY6vHi.

Once each grading agency completes its regular testing protocols, it’s required to report to the ALSC BOR the resulting data, along with any recommendations it has regarding changes to current published design values. Fortunately, changes are rare. The most significant in recent years involved SPIB and their recommended changes to the design values of Southern Pine (SP) in 2012.

Again, these published design values are integrated into component design software. The parameters of each truss assume that the lumber species, grade, and size used in the manufacturing process match the design input. This assumption emphasizes the importance of the lumber grade stamp placed on each stick of dimensional lumber that helps users identify key structural properties.

As part of SBCA’s efforts to be a contributing representative of our industry, Greg Greenlee, SBCA’s Technical Director, is now a member of the ALSC (The American Lumber Standard Committee). Through this, SBCA participates and contributes to the committee in a collaborative manner to aid in how to best address issues brought before it. The ALSC meets annually; SBCA will be attending and participating in the quarterly ALSC Board of Review meetings, as well. SBCA is at the forefront in order to best serve the industry and its members.

How Lumber is Assigned a Grade

There are various ways grading agencies determine the grade of a board of lumber, but the most common is referred to as visual grading. Traditionally, this is performed by one or more qualified people in the mill who look at all four sides of a piece of lumber, and then apply grading rule criteria and evaluate the characteristics they see to determine to which grade the piece belongs.

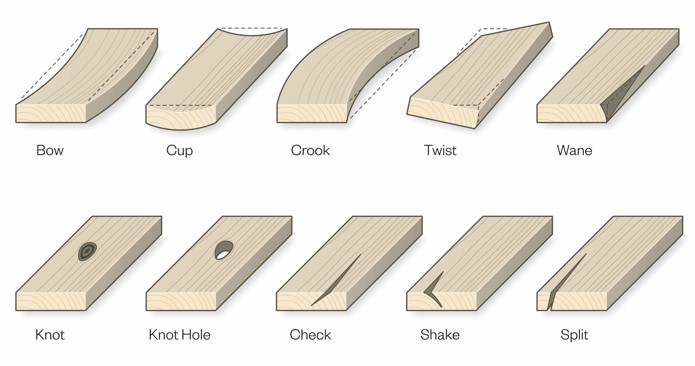

Because wood is an organic substance and no two trees grow exactly the same way, nor are their trunks cut in exactly the same configuration, visual grading rules define the size and frequency of different characteristics that are permitted for each grade (see Figure 1). The characteristics may affect the lumber’s structural strength, such as slope of grain, holes, and knots, while others may affect its appearance or ability to withstand long-term structural use (sometimes called serviceability), such as wane, warp, or skipped dressing (rough surface).

FIGURE 1: These are some of the most common defects found in structural lumber.

FIGURE 1: These are some of the most common defects found in structural lumber.

In modern mills, it is not uncommon for companies to employ machines to conduct visual grading. Using a system of lasers and camera scanners, visual grading criteria can be applied using software and these digital scanning techniques. This approach allows lumber manufacturing mills to assign visual grades to lumber without a human looking directly at a specific piece of lumber. This can significantly increase the accuracy and efficiency of applying visual grading criteria to manufactured lumber.

Since the 1960s, another common way for structural lumber to be graded is with a stress-grading machine. The ALSC has developed criteria for how machines can evaluate one or more specific characteristics of lumber related to its strength and stiffness. There are several technologies today that are employed by these machines to produce machine stress rated (MSR) or machine evaluated lumber (MEL), but the most significant difference is that a machine non-destructively tests each board during the manufacturing process to determine its physical properties.

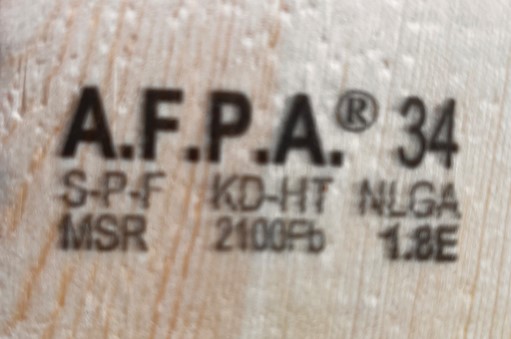

How to Read a Lumber Grade Stamp

Once a piece of lumber is assigned a grade, a grade stamp made of indelible ink is applied to its surface. A grade stamp contains specific information that allows a lumber user to reference specific published design values ascribed to that piece of lumber, as well as allow the lumber to be traced back to its source in the event of an issue.

While every board is stamped before it leaves the mill, it’s important to note that cross-cutting graded lumber into pieces that are shorter than the original piece is a very common practice in the light-frame construction industry. The ALSC system recognizes that whether the lumber is cross-cut on a jobsite or in a manufacturing facility, the shortened pieces are assumed to maintain the same grade and design properties as the original piece. Given this assumption, CMs are encouraged to have appropriate quality control procedures that will allow the grades of all lumber used in each structural component to be traced and verified.

While every board is stamped before it leaves the mill, it’s important to note that cross-cutting graded lumber into pieces that are shorter than the original piece is a very common practice in the light-frame construction industry. The ALSC system recognizes that whether the lumber is cross-cut on a jobsite or in a manufacturing facility, the shortened pieces are assumed to maintain the same grade and design properties as the original piece. Given this assumption, CMs are encouraged to have appropriate quality control procedures that will allow the grades of all lumber used in each structural component to be traced and verified.

Under the ALSC system, each stamp must be legible and contain five elements:

1. Species

While all lumber species are graded at the same four levels of strength and appearance (Select Structural, No. 1, No. 2, and No. 3), they do not have identical properties from a structural standpoint. The species of a piece of lumber will be indicated on the grade stamp with the name or abbreviation of individual species or species combination.

2. Agency Trademark

For acceptance in the U.S., six grading agencies have jurisdiction over establishing softwood lumber design values and have oversight of lumber manufacturing mills. Each of these rule-writing agencies has its own trademark. A mill will use the trademark which corresponds with the agency that monitors its grading procedures.

3. Mill Identification

Each lumber manufacturing mill will also include its own unique trademark, which is typically a number or set of letters.

4. Grade

As mentioned above, each piece of lumber is assigned a grade following either visual grading criteria or through a non-destructive test conducted by an approved machine.

5. Moisture Content

Finally, every stamp must identify the lumber’s moisture content at the time of surfacing (e.g., when the lumber surface is planed of charring after it is removed from a kiln). Green, or unseasoned lumber, is labeled as surface-green (S-GRN) and has a moisture content of 19 percent or more. Air dried lumber has been dried without a kiln and has a maximum moisture content of 19 percent and is labeled S-DRY. Kiln-dried (KD) lumber also has a maximum moisture content of 19 percent.

How Lumber Species Groups Impact Design Values

How Lumber Species Groups Impact Design Values

For CMs, the two key elements of the lumber’s grade stamp are the assigned grade and the species or species group. While this may seem straightforward, there are important differences to be aware of when using lumber from species groups.

Lumber species groups exist because it is often not practical, or potentially desirable, to separate individual species of logs when the lumber manufacturer processes them. Common species groups used in North America for structural purposes include, but are not limited to, Southern Yellow Pine (SP), Spruce-Pine-Fir (SPF), and Douglas Fir-Larch (DF-L). DF-L, for example, encompasses trees grown in three separate geographic regions in North America. The three regions are indicated on the grade stamp using the designations DF-L, DF-L(N), and DF(S). DF(S) is specific to the southwestern U.S. growing region and does not include western larch.

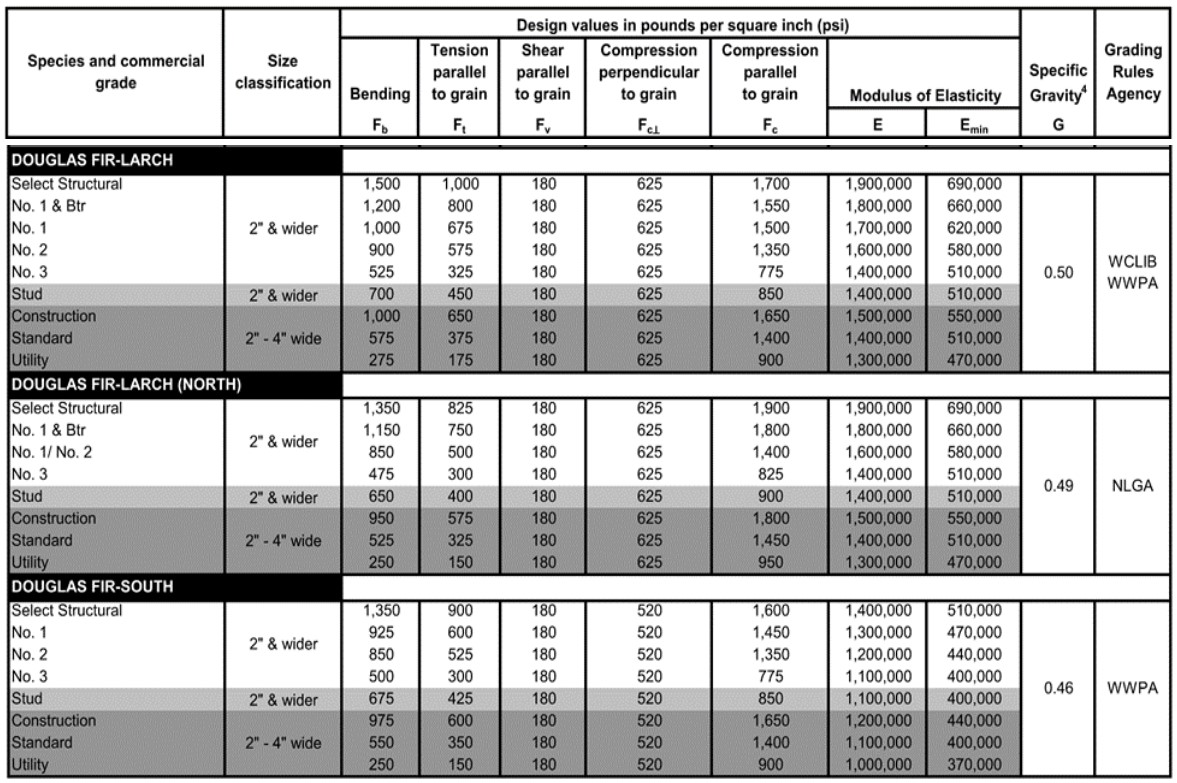

These different growing regions have an impact on the published design values under ALSC’s PS 20. Below (see Table 1) are the design values in the American Wood Council’s 2018 NDS Supplement that correspond to each of the assigned species group based on the lumber grade:

TABLE 1 Source: 2018 National Design Specification Supplement, Table 4A (www.awc.org/publications).

TABLE 1 Source: 2018 National Design Specification Supplement, Table 4A (www.awc.org/publications).

Sometimes, DF-L and DF-L(N) or DF-L and DF(S) will be combined at a manufacturing mill or at a reload operation. Because these different species groups have different published design values, CMs should treat each of these groups as separate raw materials. When that isn’t possible from a practical or efficiency standpoint, under ALSC rules the lower of the two species’ published design values must be used. Some of today’s design software platforms can handle this automatically.

How to Avoid Lumber Purchasing Headaches

How to Avoid Lumber Purchasing Headaches

CMs do not simply purchase lumber for use in their products; rather, they purchase and rely on the design values attributed to that lumber. Given this, there are a few best practices CMs can follow to ensure the lumber they receive matches their expectation at the time of purchase:

1. Specify specific species/species groups and grades at the point of purchase. Whether the buyer contacts the mill directly or works through a broker, wholesaler, or buying co-op, the buyer should be very clear in their requirement for specific grades and species/species groups. Again, species groups in the U.S. and Canada may have similar names, such as SPF and SPF(S), or DF-L and DF-L(N), but because they are grown in different regions, they have different published design values. It can’t be assumed that the seller fully understands the difference in design values.

2. Inspect all lumber bunks upon delivery. Transporting lumber from the manufacturing mill to its end destination is not always quick or straightforward. While most lumber bunks are wrapped in poly before they leave the mill, this does not mean the lumber is fully protected from the elements. Further, damage may occur during the loading, transport, and unloading process. Random pieces from each lumber bunk should be visually inspected to verify the correct species and grade on the grade stamp. Finally, it is a good practice to test the moisture content of the lumber to ensure it isn’t significantly different from what is marked on the grade stamp.

3. Clearly communicate lumber quality issues with the seller. Your customers never hesitate to inform you when there is an issue with your product in the field. Hold your lumber seller to the same standard. Communicate clearly and often when the lumber product you purchase does not meet your expectations with regard to species, grades, moisture content, or lumber quality issues such as wane, check, bow, etc.

Incorrect species, grades, moisture content, and/or quality can have a significant impact on the efficiency of a CM’s production process. Even more important, they can affect the long-term performance of a CM’s products. These lumber purchasing best practices can help reduce headaches in the manufacture, installation, and performance of structural building components.

Sean D Shields & Greg Greenlee