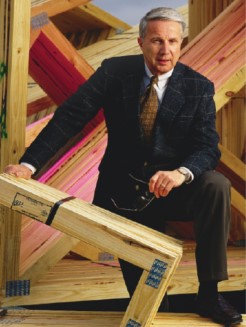

The Multi-Family Master: Trussway’s Founder Dick Rotto

Founding Fathers of the Industry, Part 2

What Cal Jureit was to the truss plate business, his customer Dick Rotto was to the apartment truss business. Both started their businesses from scratch and engineered juggernauts that still dominate their fields 50 years later. They both survived competition, recessions, and reorganizations, while still maintaining a substantial influence on building technology. The evidence of their impact on the industry is everywhere. We see it in the massive, wood-trussed, multi-family projects that were made of steel and concrete when Rotto first began. To appreciate this transformation, it’s worth examining how Rotto established his winning business model, which still drives Trussway’s success today.

Dick Rotto happened upon the first truss plant he had ever seen and left a few hours later as a partner in the business. Remarkably, he took this leap with scant prior knowledge, but with the keen prescience that would shape his future success. He also had the benefit of a telegenic partner, Charlie Barns, who, by coincidence, was one of Cal Jureit’s best customers as well as a key industry leader known for the hundreds of trailers fabricated that bore his name.

In late 1971, Rotto arrived at Barns Lumber and Manufacturing in Dallas seeking to expand his small business, which built wood playground equipment. When he saw Barns’ plant producing dozens of trusses per hour, his industrial engineering background kicked in, and he seized upon the potential this business had to offer. Because Charlie felt that the market could not support another plant, he directed Rotto to the oil-fueled building boom in Houston.

In the plant, Rotto relentlessly focused on efficiency, despite operating in a windowless structure with a single door in oppressively hot, humid Houston.

It didn’t take long for Rotto to locate a suitable building and set-up equipment similar to Barns’. By May 1972, he hung out his shingle. He brought with him from Dallas an aggressive box salesman, John Wiggs, who quickly discovered that Houston home builders wouldn’t pay a penny more for trusses than they paid for their 24-ft #3 rafters, and that their framers wouldn’t give trusses a break (and still won’t in 2022!). Rotto quickly realized he couldn’t make money in the same way his partner did, so he began to focus on commodity-priced apartment trusses. He soon learned that this sector was even more challenging, with short lead times, unpredictable schedules, and insatiable demands. To counter these drawbacks, he would have to put systems in place to create the best-cost designs, build large volumes efficiently, and deliver on time.

Establishing Systems

To address design efficiency, Rotto recruited Mark Rolf through a Want Ad in the local newspaper and capitalized on his capability to optimize trusses. Since his designs were no longer standard, and he generated additional timesharing expense to run cutting lists, Rotto abandoned mainframe-based assistance of On-Line Data, and reverted to hand calculations. His immersion in the intricacies of design gave Rotto further incentive to go after projects with long runs and avoid hip roof systems.

In the plant, Rotto relentlessly focused on efficiency, despite operating in a windowless structure with a single door in oppressively hot, humid Houston. Eventually, as the demands of the business took Rotto away from the shop floor, he turned to a renowned expert, John Houlihan, whose methods had been attested to by SBCA Hall of Famers Dave Chambers and Don Hershey. After spending weeks in the plant, Dick followed Houlihan’s advice and instituted a system that included hourly pickups and two-week master schedules, ultimately achieving maximum productivity and predictability. Yet, Rotto had the audacity to reject Houlihan’s opposition to incentive pay, extending this perk throughout his entire workforce.

But even the best laid plans and systems could be dashed by a single phone call, especially in the Wild West Houston of the 1970s. Minimal codes, flat terrain, and agreeable weather meant projects could go from permits to slabs to framing before trusses were even ready. Fortunately, the vigilance of John Wiggs, regularly scheduled meetings, and the creation of flexible support systems had an impact. Chief among these was the Project Spreadsheet, a forerunner to today’s Jobsite Packages, which facilitated on-the-fly adjustments at both ends. By late 1974, Trussway was able to successfully supply its first remote project, an apartment building project 800 miles away, in Overland Park, KS, and was well-positioned to take on new challenges.

Seizing Opportunities

A nearby project, the incorporation of floor trusses in a townhouse, presented a business-doubling deal. Immediately after a site visit, Wiggs made a sale, Rotto ordered new equipment, and Rolf began the task of designing them before TPI had agreed on standards. (The Parallel Chord Truss criteria, PCT-77, wasn’t introduced until three years later.) This entailed figuring out the details that enabled floor trusses to take the place of stick framing, and convincing framers that trusses were better than their ingrained practices.

A second pioneering breakthrough occured when Trussway rolled out its window and door components, further increasing its returns from each project.

A second pioneering breakthrough occurred when Trussway rolled out its window and door components, further increasing its returns from each project. It was the result of artful negotiations with the framer, who agreed to reduce his labor cost per square foot, and the job superintendent, who had to acknowledge his savings on lumber. It also added to Trussway’s risk, since some of the components had to carry considerable loads from multiple levels of framing, requiring a new level of expertise.

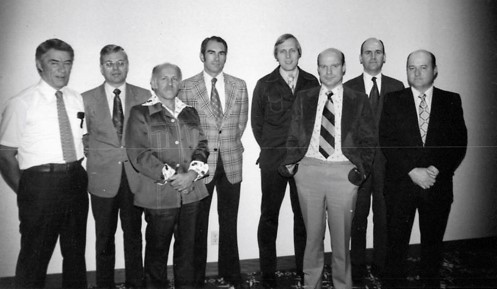

As Trussway grew, Rotto was able to pursue top talent. One of his first major hires was Gary Sweatt, PE, Chief Engineer of Clary Corporation, who was then a top machinery and engineering supplier. Sweatt had authored the first pre-computer cutting manuals and later ascended to the SBCA Presidency. Rotto then brought on board Jim Meade, PE, who had managed the largest truss design department in the industry at Shoffner Industries. Later, Rip Rogers of Barns Lumber, future SBCA President and Hall of Famer, moved into top management.

Within just 4 years of its opening, the Lumpkin Road facility was overloaded, so new property was purchased at 9411 Alcorn St., its current location. A state-of-the art facility with four times as much capacity was built and occupied in October 1977. One month later, the company bought property in Georgetown, a northern suburb of Austin, and opened a new facility in February 1978, with Gary Sweatt as President/GM. In October 1979, the company partnered with Barnes Lumber and Manufacturing Co. to open Trussway Barns, Inc.

in Ft. Worth.

Meeting Challenges

Throughout the 1970s, the record rise in oil prices fueled Texas multi-family’s rapid growth. But it also attracted outside competitors, especially because housing starts had cratered elsewhere. Large multi-plant operators such as Shelter Systems and Timber Tech set up plants on Trussway’s home turf and impacted its margins. Fortunately, the sheer volume of work at Trussway’s plants generated enough cash to sustain it for the dark days ahead.

As the decade ended, apartment construction might have been adversely affected by the steady decline of crude oil prices. However, the Economic Recovery Tax Act of 1981 relaxed lending rules, sparking a mad dash to over-build apartments in Texas. By late 1985, when oil prices hit historically low levels, apartment vacancy rates climbed, and new starts slowed. While competitors began selling at levels below Trussway’s cost, Rotto looked to other more profitable markets, and continued to expand his business.

Orlando, Florida in the 1980s was much like East Texas in the 1970s in terms of climate, terrain, and growth, but fueled by vacation resort rather than oil industry jobs. Roto selected an ideal location near the center of Orlando’s expansion, and opened a large, well-equipped plant in October 1985. By bringing Trussway’s staff, systems, and expertise to the new location, he quickly won a significant share of the apartment market. He then established a roof truss-only facility in a leased building in Cartersville, just north of Atlanta, that imported floor trusses from Orlando and Houston.

The Crash of 1986 and its Aftermath

The rapid expansion in Texas spurred by the Tax Act of 1981 was turned into a depression when the Tax Reform Act of 1986 rescinded development incentives. Since apartment building in Texas practically came to a halt, Trussway had to cut operating costs and find new markets. Salesmen were dispatched to Ontario, CA, Las Vegas, NV, Kansas City, MO, Northern Virginia, and Connecticut, while facilities were either closed or merged.

Outlying sales efforts kept business going in Houston and Ft. Worth, but national multi-family starts in those markets soon slowed, except in the nation’s capital region, where Rotto doubled his sales efforts. In 1989, Rotto began operations in a large, leased building in Fredericksburg, Virginia, solidifying his multi-family dominance up and down the East Coast.

By 1991, while many Texas truss operations failed, and new housing starts across the nation reached its lowest level, Trussway managed to survive and even thrive. Rotto accomplished this not just by capitalizing on Trussway’s savvy in the apartment sector, but also by giving generous incentives to local managers and sales teams. Over the next several years, he consolidated management and business practices, and instituted computerization. By 1995, when his long-time partner, Charlie Barns, wanted out, Rotto turned to private equity investors to fund his business. He himself left in 2000. The next five years of Trussway’s business are well chronicled in SBCA Magazine’s June-July 2005 issue. Since then, the company has weathered the Great Recession and numerous other challenges. But the highly successful Trussway of today, fifty years after its creation, looks very much like Dick Rotto’s Trussway.

About the Author: Joe Kannapell began his career in the truss industry with Hydro-Air Engineering over 50 years ago. His final promotion to Senior VP of Sales at MiTek reflected his life-long commitment to serving component manufacturers and bettering the industry. In retirement, Joe isn't slowing down. One of his passions is to record and preserve the history of our industry. This article is the second installment in his series on some of the industry's founding fathers that he knew well. If you'd like to contribute to this effort, please reach out to us at media@sbcacomponents.com.