How Will Sticky Inflation Affect Housing in 2022?

Originally Published by: LBM Exec by Greg Brooks— February 16, 2022

SBCA appreciates your input; please email us if you have any comments or corrections to this article.

Well, that escalated quickly. Sixty days ago the debate was all about how long it would take the rockstar U.S. economy to power through a brief period of inflation. Now the question is whether our impending faceplant will be epic or merely fugly.

After GDP grew 6.9% (annualized) in Q4 2021, the biggest quarterly gain in more than 20 years, “the U.S. economy is about to slam into a wall,” warns CNBC.

To be fair, 7% wasn’t sustainable to begin with. Over two-thirds of Q4 GDP growth came from rebuilding inventories. At this point “inventories are roughly back to where they should be,” says Moody’s chief economist Mark Zandi, and that leaves the economy squarely on the shoulders of consumer spending.

The good news is that employment growth is still strong. On Wednesday, February 2, ADP reported a loss of 301,000 jobs in January. That had everyone convinced that Friday’s official jobs report from the Bureau of Labor Statistics would be equally bleak. Instead, we gained 467,000 new jobs.

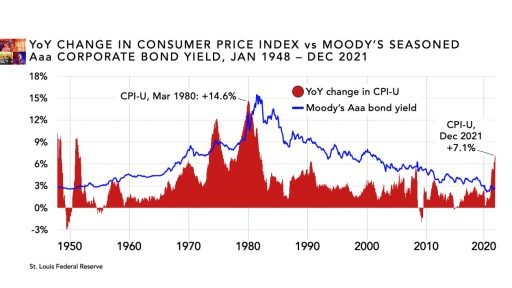

The bad news is that inflation is apparently stickier than everyone had hoped. The Consumer Price Index has been posting YoY gains of more than 5% since June. In December CPI-U was up 7.1% YoY, its highest level since mid-1982.

The Federal Reserve plans to raise interest rates in March. Speculation is that it may be the first of four or five rate hikes this year. Throw in the lingering effects of Omicron plus the potential impact of the new BA.2 subvariant and it’s no wonder the Atlanta Fed is forecasting just 0.1% GDP growth in Q1 2022.

Naturally, armchair quarterbacks are taking the field. MarketWatch worries that the Fed will raise rates too aggressively, “exacerbating the risk of a U.S. slowdown.” The Financial Times complains that “the Fed is too late to remove the punchbowl.” The two things everyone agrees on are 1) the Fed has zero margin for error, and 2) everyone has zero confidence in the Fed.

Obviously none of this is good news for real estate. Fortune is warning home buyers to “buckle up for another brutal spring housing market” as skimpy inventories plus surging mortgage rates combine to stomp affordability flat.

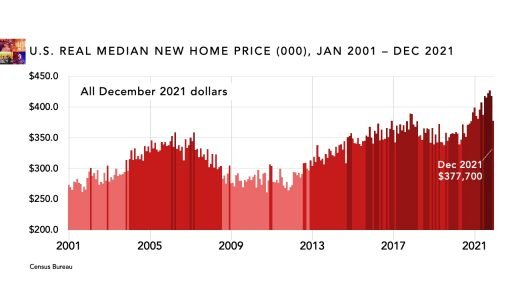

As of December, the for-sale inventory of existing homes had fallen to 1.8 months, its lowest level ever. According to Redfin, the median sale price of a home is up 14% YoY. From mid-December through mid-January, new listings were down 12% but 41% of the homes that were sold went for more than their listed price.

In December, adds Redfin, “59.6% of home offers written by Redfin agents faced bidding wars.” That’s actually down from the all-time high last April, when 74.6% of homes received multiple offers.

If bidding wars don’t heat up again this spring, chances are the reason will be that inflated mortgage rates are cutting millions of buyers out of the market.

In fact, it’s already happening. When COVID first hit, the Fed became the nation’s largest buyer of mortgage-backed securities. Now it’s backing off and selling its holdings. “Less demand for mortgage bonds means issuers must offer higher yields to attract investors,” explains WSJ. As a result, “lenders have to raise interest rates on the mortgages inside those bonds.”

The average rate on a 30-year conventional fixed mortgage was 3.55% in the week ending January 27th, up 30% from 2.73% in January 2021. NAHB’s estimates that an 82-basis-point increase means an additional 3.9 million households (out of roughly 129 million total) will be unable to qualify for a mortgage on a median-priced new home.

The obvious solution is to build more homes. We’re trying—and, in fact, making surprisingly good progress considering the state of the supply chain (FUBAR) plus ongoing shortages of labor and finished lots.

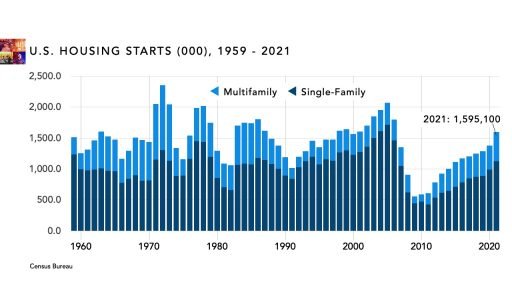

Housing starts finished 2021 at 1,595,100: 1,123,100 single-family homes plus 472,000 multifamily structures. Both total and single-family starts hit their highest level since 2006. Multifamily starts were at their highest since 1987.

Housing forecasts usually change during the year, but so far the consensus is that the party isn’t over quite yet. NAHB says we’ll see 1.625 million starts in 2022, then 1.604 million in 2023. Fannie Mae is calling for 1.632 million followed by 1.536 million. Wells Fargo thinks 1.66 million, then 1.63 million. John Burns Real Estate Consulting believes housing starts will continue to rise in 2023: 1.67 million starts this year, followed by 1.82 million.

But the price of progress is more inflation. The median hourly wage for production and non-supervisory workers employed by framing subcontractors rose 8% in 2021 and is up 11.6% versus its 2019 (pre-pandemic) level. Likewise, the average cost of a developed lot was up 35% YoY in Q4 2021 according to Zelman & Associates.

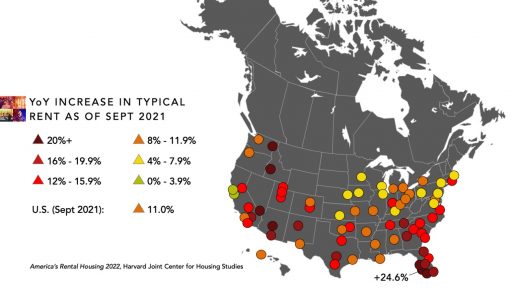

As rising home prices squeeze prospective buyers out of the market, demand for rental housing naturally increases. The problem there is—you guessed it—inflation.

In America’s Rental Housing 2022, the Harvard Joint Center for Housing Studies notes that “by October 2021, rental property prices were rising by 16.8% year over year—the fastest rate since at least the early 2000s.” And there’s more to the story than a simple imbalance between supply and demand.

The trillions of dollars in equity capital that flooded the planet following the Great Recession did not bypass the rental property market. The Joint Center says non-individual investors—private equity-backed real estate management firms, LLPs, REITs, etc.—owned 26% of the U.S. rental stock in 2018: nearly 90% of properties with more than 25 units, over 60% of those with five to 24 units, and just over 20% of single-family and two- to four-unit properties.

Since then, not only has passive investors’ market share grown, the property mix is shifting. The Joint Center says “investor entities purchased a record-high 18.2% share of homes sold in the third quarter of 2021.” Moreover, “single-family homes accounted for 74% of investors’ third-quarter purchases.”

The Joint Center report noted that “there are concerns that the new owners will raise rents aggressively,” but was hopeful that “improvements in technology and efficiency that corporate ownership might bring to the management of the single-family stock could yield cost savings that prevent a large jump in rents.”

Actually that horse is already out of the barn. Rents typically rise at a rate of 2% to 5% per year. In Dec 2021, average rent across the U.S. was up 14.1% YoY according to Redfin’s Rental Market Tracker. Austin led the charge with a dazzling 40% hike, followed by the New York City metro (+35%) and the Miami-to-West Palm Beach corridor (+34%).

In a recent op-ed, Bloomberg’s Mark Gongloff calls Millennials “America’s most economically cursed generation” for having the bad luck to come of age just in time to get hit by the dot-com bust followed by 9/11, the 2003-07 housing bubble, the Great Recession, the pandemic—and now maybe runaway inflation.

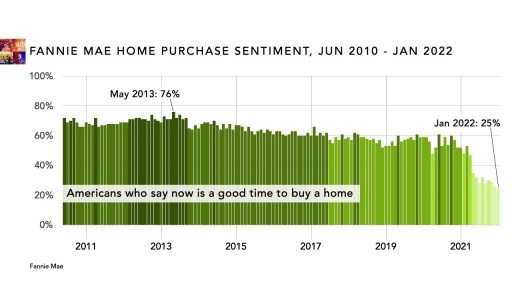

Gongloff speculates that “the housing market might be about to stick it to them once again” if they get suckered into buying a home when we’re presumably at or near the top of the market.

Fortunately, most of them aren’t. Fannie Mae’s Home Purchase Sentiment Index hit its lowest level ever in January. Only 25% of Americans think it’s a good time to buy, and just 15% of 18- to 34-year-olds agree. That’s good news. Millennials may be cursed, but here’s clear evidence that at least they’re not asleep at the wheel.

Now if only we could say the same about institutional investors.

Under normal circumstances, pension funds and insurance companies are among the most risk-averse investors you’ll find. They need to be conservative; they have future liabilities to meet.

But they also need a 6% to 7% return to meet those obligations. Historically low interest rates following the 2008-09 recession simply couldn’t provide the returns they needed.

That pushed them into private capital markets that “were once so obscure they were called ‘alternatives,’” explains The Economist. “PE—which consists of taking over companies using debt, juicing up profits and reselling them at a premium—promises racy returns.”

So far those bets have paid off, and that should probably be no surprise. The Dow Jones Industrial Average has more than tripled since the end of 2009. Apparently those successes made it look easy, though. From 2007 through 2021, the global value of assets managed by private capital firms also more than tripled, from $3 trillion to $10 trillion.

The catch is that a third of that $10 trillion is unallocated capital that hasn’t yet been deployed. Because the market is flooded with capital to invest, competition for attractive investments has spiked. Naturally that has driven multiples higher.

In turn, that has forced PE managers to look beyond familiar and well-understood industries in search of bargains capable of racy returns. The more they stretch, the riskier those investments become.

Take offsite construction, for example. When Michael Marks first approached SoftBank with the idea for Katerra, it must have looked like a no-brainer: A well-known and respected veteran of the most complex manufacturing enterprise on the planet wanted to take on an industry in which the manufacturing process hasn’t changed substantially for more than 150 years. What could possibly go wrong?

What went wrong was a detail so obscure that even most industry veterans rarely consider it. Offsite requires precise engineering; every detail of the structure has to be planned in advance. That seems like a fine idea, and it is. But it’s also expensive, and so far at least, the process can’t be automated.

In single-family construction—which is over 70% of the residential market—you can get by with a sketchy plan if you stick frame because the framers will fix all the errors and omissions in the field.

Everybody complains that “the plans suck” (as one dealer put it), but the end result is still structurally sound. More important, builders save money.

Right now, the hot ticket for PE-backed housing investors is the single-family rental (SFR) market and its cousin, build-for-rent (BFR).

Property management firms are bidding up home prices and paying cash (30% of purchases in 2021), and in some markets, buying entire subdivisions of new single-family homes for use as rentals. How can they do that? By making offers no builder can refuse. When D.R. Horton sold a 124-home suburban Houston subdivision to Fundrise last year, it literally doubled its profit versus selling to individual buyers.

The private equity buying frenzy is “exacerbating the housing shortage and driving up prices,” says real estate consultant Scott Cox, but that’s not news to anyone. The news is that, as investments go, SFR-BFR may not be a good one.

“Yields in the single-family for-rent business are actually not very impressive,” says Cox. “It’s pretty hard to find locations that will generate a 5% yield after expenses.” Cox says “investors are betting on significant rent appreciation” to get the returns they need.

So far they’re getting them. According to Redfin, the U.S. average monthly rent in Dec 2021 was $1,877. By comparison, the median mortgage payment was $1,553. That normally convinces people to buy rather than rent, and it has this time, too. One recent survey found that three out of four single-family renters intend to buy within the next three years.

The problem is finding a home to buy, and that gives SFR investors leverage. They talk about people who can afford to buy but prefer to rent, but Cox says investors are willing to bet on rent hikes “because they fundamentally believe our society will not get its act together in the housing space and address our problems.”

Maybe we won’t. But it seems unlikely that Warren Buffett (“be fearful when others are greedy”) or John D. Rockefeller (“buy low and sell high”) would approve of an investment strategy that consists of buying homes en masse at all-time record high prices so you can lease them at all-time record high rents.

In effect, investors are betting that NIMBY resistance to development is stronger than all the market forces pushing to rebalance supply and demand. And there are a few of them.

New household formation—i.e., the pool of prospective renters—actually turned negative in 2020, and COVID was just the tip of the iceberg. According to Pew Research, U.S. household growth throughout the past decade has been at its lowest level in recorded history. Records go all the way back to the Civil War.

Plus, housing starts are rising despite all the obstacles builders are facing. At the current pace—or anything close to it—for-sale inventories should rebound sooner rather than later, especially with household growth at an historic low. That’ll bring home prices down and undercut demand for rentals.

At the moment, the supply chain is a drag on new construction. By all accounts it’ll have itself sorted out within a year. As it does, material prices and availability will fall back to at least something resembling normal, which will improve affordability and help boost production.

And don’t forget inflation. Home prices are high partly because mortgage rates are so low. When rates go up, prices usually fall to compensate for the increase.

But there’s another interesting twist: If inflation persists, it may undercut private capital markets. More than a few housing industry veterans would say that PE investors appear to be flying blind in this business. If so, it stands to reason that they’re probably also groping in other industries where their experience is limited.

As bond yields rise, we’ll reach a point where institutional investors are once again able to achieve the returns they need with traditional investments. That’ll motivate some to take a harder look at their investments in the private capital market.

A few high-profile failures in industries that are unfamiliar to PE managers could well convince institutional investors that PE in general is too risky. If so, we might see a stampede out of private capital that is every bit as impressive as the stampede in during the 2010s.

It’s all speculation at this point. But if it happens, chances are it’ll escalate quickly—and 85% of 18- to 34-year olds will be cheering it on.