New Study Looks at Impacts to Construction Labor Wages

Originally Published by: Gordian — January, 2024

SBCA appreciates your input; please email us if you have any comments or corrections to this article.

For those trying to manage construction costs in the U.S. market, relief is always just out of reach. After several years of sustained volatility in material cost and availability, inflation is cooling and markets are stabilizing. However, concerns loom in a new area — labor. Since the start of the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020, a series of factors have caused significant friction in the construction labor market. Alas, industry stakeholders have traded one crisis for another.

Rising Tides Lift All Boats

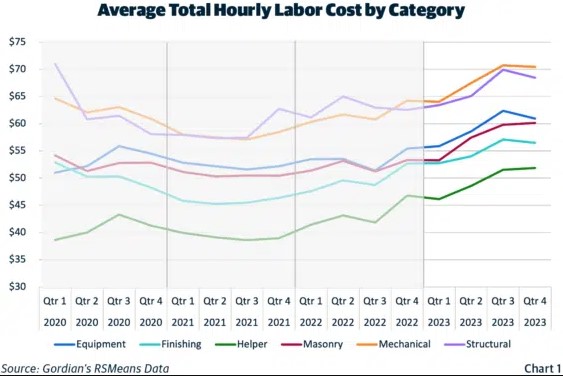

From 2021 through 2023, the Consumer Price Index (CPI-U) showed the highest sustained inflation in the U.S. economy since 1981. In the same period, elevated spending in the form of the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act (IIJA) generated significant labor demand for major projects throughout the United States. Construction wages began increasing to match both the surge in demand and general inflation, rising an average of 20% from 2021 to 2023. See Table 1 for a detailed breakdown by category.

Table 1: Average Wage Growth by Trade, 2021 to 2023

Two major changes in construction labor dynamics at the federal level will compound these increasing cost structures in 2024 and beyond. The first occurred in February 2022 when, by Executive Order, Project Labor Agreements (PLAs) were mandated for all federally-funded projects with contract values above $35 million. These individual project agreements with organized labor have been estimated to increase large project labor costs between 12%-20%. With up to 40% of the $34 billion of federal construction put in place affected by the institution of PLAs, contractors can expect to see added labor cost increases across the board.

The other major change to labor costs will have a more meaningful effect in many areas. In 2023, the Department of Labor overhauled the Davis-Bacon Act. Among many changes, the most impactful to costs will be the return to the “3-step process.” Since 1983, prevailing wage has been calculated using only two steps:

- The wage rate paid to a majority of workers in the classification, or

- If no rate is paid to at least 50% of workers, then the weighted average rate in the classification.

By reinstating the 3-step process, the prevailing wage is calculated as follows:

- The wage rate paid to a majority of workers in the classification, or

- If no majority exists, the rate paid to 30% of workers, or

- If no rate paid to at least 30% of that classification’s workers, then the weighted average in the classification.

The overhaul also changed the mechanisms by which urban and rural wages are differentiated and updated between survey releases.

With an estimated 1.2 million workers in the construction industry affected by these changes, over time Gordian predicts that the new third step will increase wages in those areas with moderate-to-weak labor union presence, as their wages, defined by collective bargaining agreements (CBA), will have more weighting power in establishing prevailing wages. Additionally, with more frequent and indexed updates to rural prevailing wage estimates, wages for rural laborers are expected to increase faster than in the prior calculation regime.

These regional disparities in labor costs have already begun to surface across the United States. Construction trade wages in the continental U.S. have been steadily rising at a much higher rate in traditionally low-cost areas. See Map 1 below.

Map 1: Install Cost Growth, 2018 to 2023

Businesses find themselves in the unenviable position of paying more per hour for labor while getting less output per labor hour.

The Rise of the Mega-Project

Mega-projects, defined as those over $1 billion in size, have become a larger part of the non-residential construction market than at any point in recent history. Prior to 2020, mega-projects generally constituted around 15% of all nonresidential construction spending; that figure has since risen to closer to 30%. Such projects have become a principal driver of the industry’s rapid growth since COVID. However, they also bring with them certain challenges.

Mega-projects can overwhelm locally available resources, in particular labor. This is especially true when multiple uncoordinated mega-projects are located within close proximity to one another. Such a scenario will readily stretch the available supply of general and specialty construction labor, driving up the cost of construction in the region. According to data from the White House, states between Michigan and Georgia will likely be the most impacted by mega-projects. However, metropolitan areas from coast-to-coast will experience volatile demand for labor and materials as a result of areas of concentrated mega-project activity.

Map 2: Mega-Projects Source: https://www.whitehouse.gov/invest/

Source: https://www.whitehouse.gov/invest/

These mega-projects and major infrastructure investments are increasing labor costs and decreasing the skilled labor pool across the country. Maintenance and repair on existing assets have been hit particularly hard. A significant backlog of deferred maintenance accrued during the COVID-19 pandemic and subsequent supply chain crunches are now at risk of further delay due to labor shortages. Many strategic responses, such as material substitutions or maintenance modifications, are simply deferring costs into the future, which may not be a viable response unless structural changes occur in the labor market.

Post-COVID, construction companies have been left with a structurally different pool of laborers without having the time to adapt their practices accordingly.

Workforce Demographics

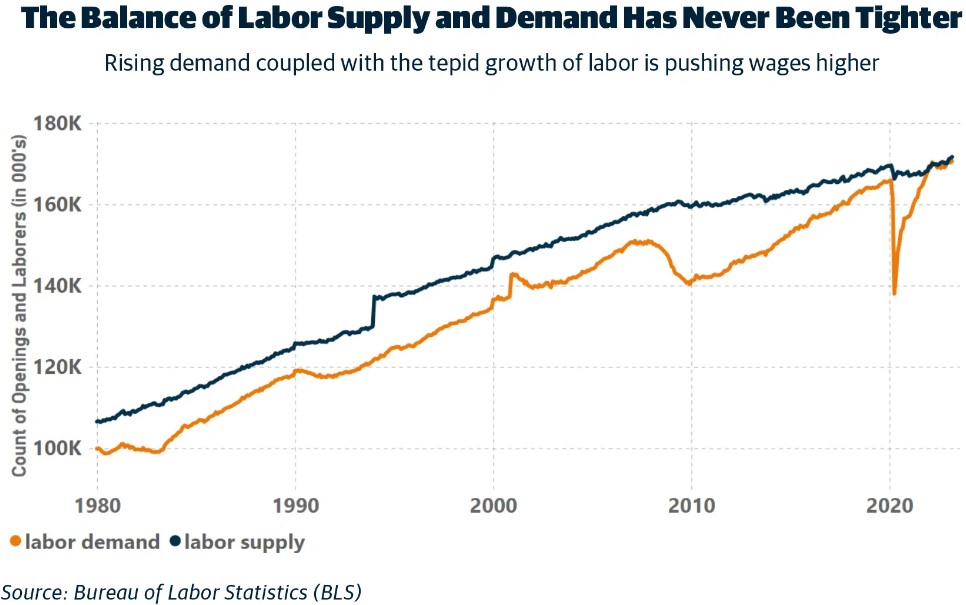

America’s current workforce crunch is not the result of a single problem, but rather the accumulated result of multiple latent problems whose consequences were sped to their tipping point by COVID, but not because of COVID. Traditionally, the gap between labor supply and demand has been a positive one, with excessive laborers ready to fill fluctuating levels of available openings. During the past 50 years of economic booms, temporary surges in the quantity of labor demanded have narrowed this gap, but never exhausted it. During these previous “squeeze” periods, wages increased by 5% annually. It would not be until the fourth quarter of 2021, six months after the third round of government stimulus checks had gone out, that strong consumer demand and disrupted supply chains would see that gap collapse for the first time in recorded history.

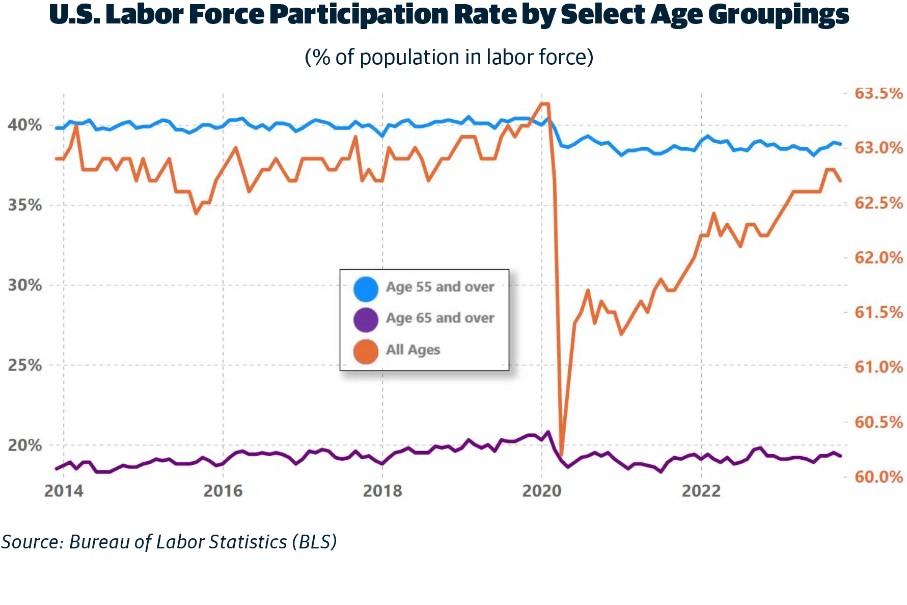

The government’s efforts to stimulate the economy through consumer spending resulted in the creation of an astounding 28 million new jobs in 18 months. At the aggregate level, these were enough new jobs to replace those lost during the pandemic. However, the plan was too blunt an instrument to address the ensuing skills mismatch. As a result of the economy’s initial COVID shutdown in early 2020, over one million Baby Boomers, many with decades of work experience, permanently left the workforce.

In the three years since, the percentage of the over 55-years-old working population has not made a meaningful recovery from the pandemic. There is no expectation of this cohort returning to the construction labor force. The result is that, post-COVID, construction companies have been left with a structurally different pool of laborers without having the time to adapt their practices accordingly. It is this mismatch between jobs and workers that explains why businesses find themselves in the unenviable position of paying more per hour for labor while getting less output per labor hour.

Nor are additional labor sources on the way to solve the problem. A historically high proportion of those between the ages of 25 and 54 are already engaged in the workforce. Attempts to encourage more American-born people from this cohort to join the construction labor pool will produce underwhelming returns and/or come at a steep price. Similarly, businesses should expect little relief from immigrant labor. In 2022, 18% of the U.S. workforce was composed of foreign-born workers, a record high. That year’s immigrant labor unemployment rate, 3.4%, was even lower than the nation’s overall rate.

Adapting to the New Construction Workforce

The severity and structural protractedness of today’s labor shortage means that businesses that hope to wait out today’s imbalance of worker supply and demand may be stalling for an impossibly long time. According to the Bureau of Labor Statistics, the average construction worker was approaching 43 years old in 2022, a gain of over seven years compared to 1994. Alternatively, there are proactive options, any one or several of which could be highly rewarding in the long-run as companies search for — and find — efficient ways to achieve yesterday’s output with today’s workforce.

1.) Leaders Must “Own” Their Company’s Training and Development Program

Company owners must approach labor training and development with a combination of external and in-house efforts. In-house training ensures that employees are learning exactly the skills which are most pertinent and important to your company’s success. It also creates natural opportunities for your company to share and teach employees about the company’s culture, ethics, mission and vision; in short, what it takes for them to succeed at your firm. External offerings, by comparison, may not provide new recruits with the complete education you desire, nor teach them what it takes to meet your expectations and succeed at your company. The worst thing that can happen to your business is not that you train someone and they leave, but that you don’t train someone and they stay.

2.) Encourage Employee Longevity

Just as important as providing a quality education is making sure your company is an attractive place for employees to work. More than ever, you have to make them want to stay. Employee longevity is only minimally impacted by wage compensation. Pay may get employees to clock-in, but it only weakly influences their engagement and willingness to work. Employees should have career pathing discussions with management. Once employees understand their range of possible futures within your firm, encourage them to select a path forward and then help them achieve their career goals. This gives both sides a common vision that allows for mutual success.

3.) Set Up a Referral Program

When properly trained and set on a career development path, your employees are your biggest advocates. They likely know someone who is either actively looking for a job or who isn’t satisfied with their current situation, so why not reward them for referring new talent? Offer cash or a desirable reward, as regulations permit, when current employees refer a new hire who makes it through your firm’s standard probationary period.

Additional sources for referrals are your friends and family, your professional network and the companies you do business with, from subcontractors to material suppliers. Don’t overlook social media. If you’re on sites like LinkedIn, Facebook and X (formerly Twitter), be sure to let your connections know you are hiring.

4.) Expand Your Circle: Hire More Women

The number of women in the construction workforce is growing many times faster than that of men. In the 12 months ending July 2023, the number of women in the workforce grew by 6.5% while the number of men was nearly flat. Despite being outnumbered 7-to-1, the growth of women in construction since the beginning of 2021 has accounted for 260,000, or nearly 1/3, of the total growth of the U.S. construction labor pool.

5.) Invest in Technology

Today’s many new construction technologies serve as an essential avenue by which firms can do more with fewer people. Developers, architects and contractors can work together to build structures that take advantage of labor-saving designs and construction methodologies. Keeping up to date on the latest construction products and innovations can improve the speed and ease of construction. The improved productivity of your employees from these efforts will help keep your company cost competitive and profitable.

Concluding Thoughts

- America’s demographics tell us with certainty that labor will be a long-term constraint on the growth of the construction industry. Barring a massive inflow of immigrant labor skilled in modern construction practices (which is nearly impossible, probabilistically speaking) the competition for labor will fundamentally alter firms’ ability to compete and win.

- It is important to realize that as the gap between supply and demand narrows, the rate of construction pay increases. As the gap narrowed in the years leading up to 2008, average hourly construction wages ramped upward, hitting a 5% crescendo just before the market crash. As the gap narrowed again between 2011 and 2019, we also saw annual pay rise at an accelerating rate. Applying the knowledge of past dynamics and coupling it with our forward-looking understanding of labor supply makes it clear that labor wage growth is a structural problem for the industry. This issue will be exceedingly difficult to resolve without the creative application of new methods and technologies. The status quo is untenable.

- The limited growth potential of the specialty contractor workforce, due at least in part to higher training and certification standards, creates a barrier to entry for business competitors. Yet history has rewarded the firms who surmount such barriers with steadier revenues and greater profitability.

- Changes in construction practices can move the needle in either direction. Although regulatory and environmental impact concerns may increase overall construction costs, firms that embrace structural change and implement modern technologies for recruiting, training and jobsite safety will see reductions in long-term labor costs.